Most of us would have known about Egyptian hieroglyphics. Not many, however, would have associated Sarawak with this writing system. Fewer still are even aware that it exists.

Enter the turai.

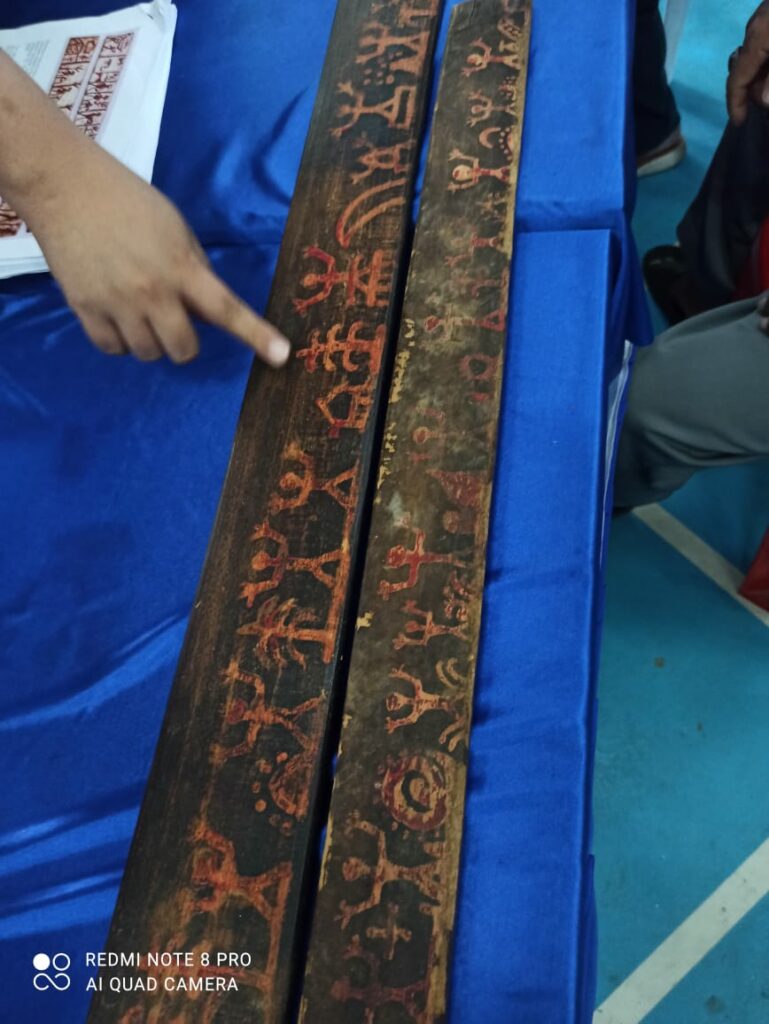

Caption: Papan Turai Gawai Batu. This papan turai was created by Imban Ak Kutak and discovered in 1963 by researchers Tom Harrison and Benedict Sandin. It has 25 hieroglyphic characters.

Turai is the purported written language of the Iban. It consists of a series of pictorial symbols that are usually engraved on a papan turai (Iban Writing Board).

Papan turai is typically used to assist in the recitation of pengap (Iban folklores) and timang (invocations) during the Gawai Batu ceremony. The board is also used to teach novice Iban lemambang (shaman), providing an intermediate between oral traditions and writing.

More importantly, papan turai records the civilisation history of the Iban people. It presents evidence of the migratory history of the Iban from the Kapuas region in Kalimantan to settlements in Sarawak as well as the genealogy (tusut) of the Iban people.

Due to its association with Gawai Batu – a ceremonial practice to ensure successful paddy cultivation – the practice of engraving hieroglyphs on papan turai is estimated to be about 400 years old (see Leo Nyuak and Edm. Dunn, 1906).

There are still many things that we do not know about the turai, and we risk losing this heritage altogether if it is not preserved. This prompted the Sarawak Museum, led by Aldrin John Hew, to conduct a study on this.

Associate Professor Dr Norazuna Norahim from the Faculty of Education, Language and Communication, UNIMAS, as one of the research team members, went with a team recently to the coastal city of Miri, Sarawak to interview Iban lemambangs, the key players in the creation and usage of papan turai.

They met two lemambangs, Unsa Ak Meringai and Unsa Ak Meringai, who helped them understand the meaning of the hieroglyphics inscribed on the Papan Turai Gawai Batu. The team also discovered another two-piece mnemonic board belonging to Mapan Ak Basik.

“It is very interesting,” Dr Norazuna enthused. “Even though they (the lemambangs) created the boards individually, the hieroglyphics are quite similar, and the two lemambangs could understand the papan turai produced by Imban Ak Kutak. We really need to study and document the semiotics of the hieroglyphs.”

Caption: AP Dr Norazuna Norahim (far left) with the research team in Miri

Why is this important, we asked (other than the exciting potential of making a film showcasing mystery writing and treasures, of course)?

Dr Norazuna explained, “The existence of such “writing systems” in the pre-literary period in various parts of the world enables the recording and communication of information. The existence of the papan turai and its hieroglyphics indicate the development of the Austronesian civilisation way before the introduction of the writing system to the Iban people.”

“The hieroglyphics are also important to clarify our history. For example, we found that all the pengaps mention Ambau, who was a pioneer chief who crossed over from Kapuas and settled in Batang Lupar. Some hieroglyphs mention the rivalry between tribes in the Kapuas region. We need this kind of information to fact check and enrich our knowledge of our own people, our own history.”

While papan turai may not be a household term yet, there has been ongoing interest in this.

In 1947, an Iban scholar, Dunging anak Gunggu, even created a writing system that is related to the turai hieroglyphics, but this is not a well-known fact, even amongst Sarawakians.

Here’s hoping that in the future, more of our local researchers will be proud experts in this area, thereby ensuring that our ancient knowledge and skills will not be reduced to memories and myths.

Prepared by: Dr Ernisa Marzuki, Faculty of Education, Language and Communication.