By Dr Noratikah Mohamad Ashari (Deputy Dean of Industry & Community Engagement, FELC)

If communication were simply about saying things clearly, universities would not spend so much time explaining strategies that had already been announced. The issue is rarely the wording but the thinking around it, and whether that thinking connects to how people actually live, work, and decide.

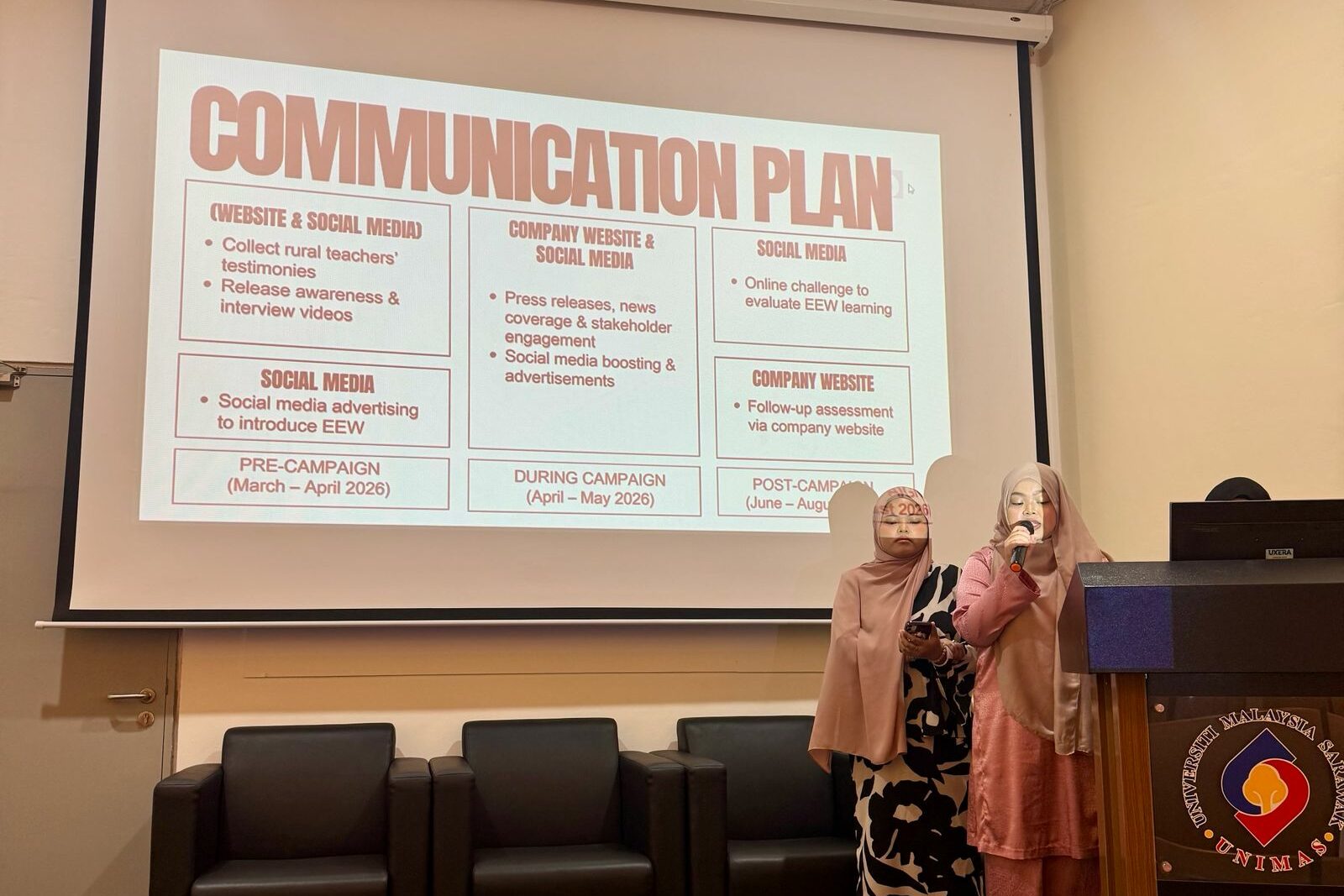

That observation framed a recent session at the Faculty of Education, Language and Communication (FELC), Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS). The session was part of an alternative assessment for the Principles and Practices of Strategic Communication course offered to second-year Strategic Communication undergraduates at FELC.

Instead of teaching students to speak louder, design better slides, or chase the right platform, the session was about helping them see communication for what it really is: a way organisations decide, justify, and move forward.

It felt like a professional conversation that happened to take place in a classroom. They were asked to explain their thinking. Why this idea? Why now. Why this approach and not another? Strategic communication, as they quickly learned, is less about expression and more about judgment.

This is hardly a new provocation. Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980), the brilliant communication maven behind the popular adage “the medium is the message,” believed that how something is communicated often matters more than what is being said. Put plainly, message delivery influences how it is understood. A deck, a memo, a tweet, or a briefing-room conversation does very different kinds of work, even when the words are the same. Strategic communication lives in that difference. It pays attention to context, timing, and environment, especially now, when algorithms often decide what people see before leaders decide what to say.

The session took on a sharper edge with Rizal Zulkapli in the room. Rizal, who was the CEO of TVS and is now the General Manager of Corporate Communications at OCI TerraSus, came to question. Students were pushed to defend their ideas as if they already belonged in the real world, where attention is limited, and clarity is currency.

The questions were deceptively simple. Who are you really talking to? What problem are you actually solving? What is the highlight of the communication plan – the event itself or the big message? What is the big message? Does the budget reflect what is actually being invested in? How do you measure your wins?

These questions feel familiar because we live with their consequences daily. We see policies misunderstood, technologies feared, and announcements backfire because the communication environment was treated as neutral, when it never is.

This is where McLuhan feels uncomfortably current. Our media landscape rewards speed, reaction, and certainty. Strategic communication slows things down just enough to ask whether the system itself is working for or against the intention. It is not about resisting technology or romanticising the past. It is about understanding that tools change behaviour, often quietly.

Having industry experts in the classroom reflects something FELC takes seriously. Industries and communities are not treated as occasional guests, but partners in how learning is grounded. They introduce friction, realism, and perspective. They remind us that communication does not live in theory alone, but in organisations, communities, and consequences.

It is one of many deliberate efforts to mentor UNIMAS students as responsible communicators in a community-driven university. These are graduates who will eventually communicate everything from ideas to science to finance, across disciplines where clarity and consequence matter equally.

This also matters as the university looks toward 2030. Behind the infrastructure, systems, or plans, our readiness is also about coherence. Can priorities be aligned? Can decisions be explained clearly? Can change be carried out without constant repair work? Strategic communication provides the connective logic that helps ambition translate into action.

The session with Rizal was a small but telling signal of that readiness. Students were asked to think (and plan) before they speak. Industry and academia met on common strategic ground, where communication is treated not as an afterthought, but as part of how decisions are made.

At FELC, we aspire to produce communicators who understand context, carry responsibility, and make complex things intelligible without flattening them. When done well, strategic communication does not decorate knowledge. It connects it, and makes it matter.

And before anyone wonders, yes, this piece was written with the help of generative AI. It drafted efficiently, stayed polite, and did not interrupt. It also did not decide what mattered. That responsibility remains human. After all, tools shape messages, but they do not excuse us from thinking. I think McLuhan would approve.