By Dr. Joseph Unja, Cohort 13, Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) candidate, UNIMAS

Let’s be honest, when we first signed up for the Thailand academic trip, many of us were just hoping for a short breather from thesis deadlines. But what we gained was far more than a break. It became a once-in-a-lifetime academic journey, filled with meaningful insights and unforgettable moments shared among us, Cohort 13 of the Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) programme at Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS).

Our academic itinerary was carefully planned and organized to maximize learning, however, in short time of visit. We visited several key institutions, including the Ministry of Public Health Thailand (MOPH) in Nonthaburi Province, the Pathum Thani Provincial and District Health Office, Bueng Yi Tho Medical and Rehabilitation Centre, Chulalongkorn University College of Public Health, and King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital.

A Warm Thai Welcome at Ministry of Public Health

Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Thailand. Their motto is “Mastery, Originality, People-centred, Humility”.

Cohort 13 students’ early morning group photo at the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand with our lecturers, Prof. Dr. Jeffery Stephen and Prof. Dr. Cheah Whye Lian

(note: some of us still stuck at traffic jam similar to Kota Samarahan!).

Our first destination was the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) in Nonthaburi. You might expect suits or stiff handshakes, but we were greeted with genuine warmth and hospitality. Thai officials, including Dr. Kittisak Agsornwong – the deputy Minister of Public Health and Dr. Komain Tewtong – the Deputy Director of the Bureau of Primary Care Support and Medical Officer at MPOH, walked us through how Thailand’s health system is structured.

Engagement session at the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), Thailand with Dr. Kittisak Agsornwong (centre) and Dr. Komain Tewtong (left of Dr. Kittisak).

And all of us can agreed that it’s a system that really focuses on making sure everyone, everywhere gets care, whether they live in a city or a tiny village. Thailand has three major health insurance schemes covering government workers, private sector employees, and the general public (refer to table below).

| Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) | Social Security Scheme (SSS) | Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) | |

| Scheme nature | Privilege benefit | Mandatory | Citizen entitlement |

| Beneficiaries | Government employees, dependants, and retirees | Private sector employees | The rest of population not covered by CSMBS and SSS |

| Coverage | 5.2 million (7.7%) | 13.1 million (19.4%) | 48.8 million (72.2%) |

| Source of finance | Tax funded | Tripartite contribution | Tax funded |

| Benefit package | Comprehensive care | Comprehensive care | Comprehensive care + prevention and promotion activities for all Thai people, including those not under UCS |

| Managed by | Ministry of Finance | Ministry of Labour and Welfare | National Health Security Office (NHSO) |

(adopted from Dr. Komain’s presentation)

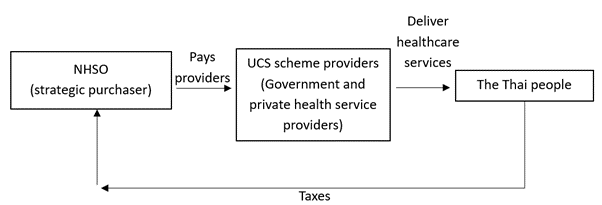

Their Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) makes sure everyone has access to affordable healthcare. And instead of one single agency doing everything, Thailand has the National Health Security Office (NHSO), which handles the money and contracts out services. It’s like ordering from Grab then NHSO finds the best provider for your health “order,” so patients get quality care wherever they are.

Wait, Who Buys Healthcare?

NHSO is what they call a strategic purchaser. It collects funds (through taxes) and pays healthcare providers based on performance. That means hospitals and clinics, even private ones, get paid fairly—but must deliver good care. It’s efficient and it helps reduce waste.

This purchaser–provider split is a major distinction from Malaysia, where the Ministry of Health (MOH) currently manages everything, both funding and service provision. Efficient, maybe. But Thailand’s method shows us a new way; more choice, more competition among providers hence more quality and efficient health services to Thai people. In 2023, Malaysia’s Health White Paper proposes moving toward a similar structure through the creation of an independent health strategic purchasing agency.

MOPH Trains the Workforce for Rural Care: Through Praboromarajchanok Institute

We also met Dr. Rajin Arora, the vice president from the Praboromarajchanok Institute, an academic institution belongs to MOPH, responsible for training a large portion of Thailand’s health workforce. The institute plays a crucial role in producing nurses, doctors, and allied health professionals for deployment, particularly in rural and underserved areas. Alongside this, public and private universities like Chulalongkorn University, Rangsit University, and Siam University also contribute significantly to Thailand’s robust health manpower.

Visit to Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), with Dr. Rajin Arora from the Praboromarajchanok Institute, gave a special lecture on human resource development for primary health care.

Legal Backing: How Thailand Strengthens Primary Healthcare

Another highlight from Day 1 MPOH visit, was learning about Thailand’s Primary Health System Act 2019, a law that enshrines the right to accessible, community-based primary care. It mandates the involvement of family doctors, health centres, and village health volunteers in delivering health services at the grassroots level. This legal framework ensures continuity, protects resource allocation, and empowers local governance. Malaysia, in contrast, currently relies only on health policies (which lack the legal weight of an Act) ensuring the structure or resources for primary healthcare, making it more vulnerable to changes in government priorities.

Cover page of the manual for Thailand’s Primary Health System Act, 2019.

Decentralisation of Health: Insights from Pathum Thani Public Health Office and Bueng Yi Tho Medical and Rehabilitation Centre

We continued our learning journey at the Pathum Thani Provincial Public Health Office and later at the Mueang Pathum Thani District Health Office. In Thailand, the provincial level is similar to Malaysia’s state level, while the district level corresponds to Malaysia’s district health offices (Pejabat Kesihatan Daerah). The subdistrict level in Thailand refers to smaller administrative units called “Tambon,” which have their own health-promoting hospitals or health centres. Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospitals (SHPH) and health centres operate directly within communities.

Thailand’s system also integrates over a million Village Health Volunteers at the grassroots level, enhancing community health engagement. This almost the same community-based concept with Malaysia’s Village Health Representative (Wakil Kesihatan Kampung) from each village, especially in rural areas.

Dr. Katakew, the deputy director of Pathum Thani Public Health Office, and Mr. Phonchai Praditphu, the director of district public health office welcomed us and gave their presentation on respective day of our visit, about their office roles and responsibilities.

Pathum Thani Provincial Public Health Office visit with Dr. Katakaew Chuaykhan, the deputy director and her dedicated team.

District Public Health Office, Mueang Pathum Thani District visit. With Mr. Phonchai Praditphu, the director and his dedicated team.

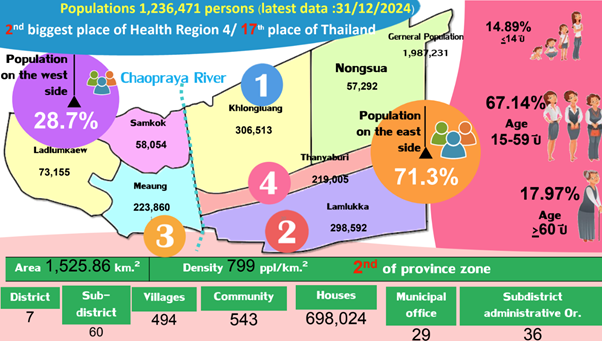

This (refer to next diagram) demographic and administrative infographic of Pathum Thani Province, updated as of 31 December 2024 showed that this province is densely populated with 60 subdistricts, 543 communities, and nearly 500 villages. As such, decentralisation of primary healthcare and community outreach remain essential.

With nearly 18% elderly population, there is a growing demand for elderly-friendly health services, rehabilitation, and chronic disease management.

In Thailand, the health system works well at the local level because of its Decentralization Act 1999, which gives more power to local authorities, such as municipalities (local government in urban areas) and subdistrict administrative offices (SAO) (for rural areas), to help manage healthcare services. The presence of municipal offices and subdistrict administrative organisations (SAOs) supports community-level governance, which is critical for Thailand’s decentralised health model. Collaboration between health facilities, SAOs, and village health volunteers can ensure better health promotion, prevention, and service accessibility across both urban and semi-rural areas.

A Local Health Centre… with Karaoke?

A standout example is the Bueng Yi Tho Medical and Rehabilitation Centre, operated under the local municipal authority. It is a health centre managed by the local government, specifically under municipal authorities (local administrative organisations), not directly under the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH). MOPH still plays an oversight and technical support role, but the day-to-day operations, management, and budget for centres like Bueng Yi Tho typically fall under the municipal or subdistrict level, as part of Thailand’s decentralisation policy.

Bueng Yi Tho Medical and Rehabilitation Centre visit with the mayor of Bueng Yi Tho municipality.

This health centre that owned by local government serves as a model for primary healthcare delivery, combining modern medical services, traditional medicine, and comprehensive elderly wellness programs. The facilities reflected Thailand’s forward-thinking approach, especially in catering to their ageing population.

They were so innovative in taking care of their elderly that they invented ‘Old People Café’- space is designed as a social and recreational area where older adults can gather, chat and most importantly…… sing karaoke! These social spaces keep the elderly mentally, emotionally, and socially healthy. It’s a perfect example of how health isn’t just about medicine, it’s about happiness, too.

Now, here’s something we didn’t expect to find on a public health trip: a karaoke session with elderly folks.

Chulalongkorn University: Where Education Meets Innovation

On our final day, we visited Chulalongkorn University, Thailand’s top public university, and its College of Public Health Sciences. Faculty members shared valuable insights and expressed interest in future collaborations with UNIMAS, citing our similar demographic and geographical challenges.

We then toured to Faculty of Medicine at the Chulalongkorn University, and King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital (KCMH), a non-profit tertiary hospital operated by the Thai Red Cross Society. Despite being an independent organisation, KCMH serves as the main teaching hospital for Chulalongkorn’s Faculty of Medicine. This partnership exemplifies the “One Chula” concept, where different units of the university work collaboratively for public good.

We were impressed by KCMH’s use of technology: self-check-in kiosks (first picture), automated blood pressure and height measurement stations (second and third), and integrated health records, all contributing to smoother patient experiences. It was a clear display that Thailand is embracing digital solutions to improve healthcare efficiency.

Beyond the Academic: A Taste of Thai Culture and Adventure

No global health experience is complete without cultural immersion. Our journey took us to Kanchanaburi Safari, the Death Railway, the floating market and the iconic Wat Arun temple. These visits helped us understand the heart of Thai society – resilient, community-oriented, and deeply respectful of history and tradition.

From chaotic giraffe feeding at the safari to eating together local dishes at be it street market or local shops, the experience bonded us not just as students, but as future public health professionals with a shared global perspective.

What We Took Home (Besides Thai Dried Mango Snacks)

Sure, we came back with bags of Thai dried mangoes and some souvenirs. But what really stuck with us wasn’t in my luggage, it was the shift in perspective.

This academic trip to Thailand wasn’t just about observing another country’s healthcare system. It was about understanding how the structure and culture shape the way a nation takes care of its people.

Their Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) and the National Health Security Office (NHSO) reflect a clear message: healthcare is a right, not a privilege. The system is strategically designed to serve everyone, with smart financial mechanisms, wide coverage, and thoughtful integration between national and local levels.

Another big takeaway? Decentralisation in action. It reminded us of how Sarawak is also pushing for more autonomy in managing its own health affairs. Seeing how this in Thailand made some us think, maybe it’s not just possible, maybe it’s necessary.

Even more impressive was how Thailand’s public health approach is supported by legal frameworks, not just policy memos. Their Primary Health System Act 2019 gives long-term strength to what would otherwise be fragile aspirations.

And here’s one part we really admired but don’t hear about enough: how much Thailand cares for its health staff. Their commitment to staff well-being isn’t just a slogan—it’s embedded in their work culture and even in their mottos. Happy, supported workers make stronger systems. That’s a lesson worth bringing home too.

So yes, we returned with snacks, but more importantly, we returned with stories, new perspective and inspiration. These are the things we should unpack, reflect on, and maybe, just maybe, use to build something better back home.

Gratitude

We would like to express my heartfelt thanks to the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (FMHS), Prof. Dr. Asri bin Said, for his leadership and support. Our sincere appreciation also goes to our course coordinators, Prof. Dr. Jeffery Stephen and Prof. Dr. Cheah Whye Lian, Head of the Quality Unit at FMHS, for their unwavering guidance throughout this journey.

A huge thank you to the Ministry of Public Health Thailand (MOPH) in Nonthaburi Province, the Pathum Thani Provincial and District Health Offices, Bueng Yi Tho Medical and Rehabilitation Centre, the College of Public Health Sciences and Faculty of Medicine at Chulalongkorn University, as well as King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Your warm hospitality, openness, and generosity left a lasting impression on us.

Special appreciation to Dr. Michael Pui and his team for organising such a meaningful and eye-opening trip, and to Dr. Sulastini for curating the thoughtful and fun non-academic itinerary that balanced learning and laughter.

And of course, thank you to all my fellow DrPH Cohort 13 classmates. This experience wouldn’t have been the same without your energy, reflections, and shared moments. Together, we made memories that will last a lifetime.

ขอบคุณ! Khop Khun Krap! (Thank you!)

Yours sincerely,

Dr. Joseph Unja

Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) Candidate

Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS)

DrPH Cohort 13 “Visibility for Viability”

08/07/2025