By Dr Nur Auni Ugong

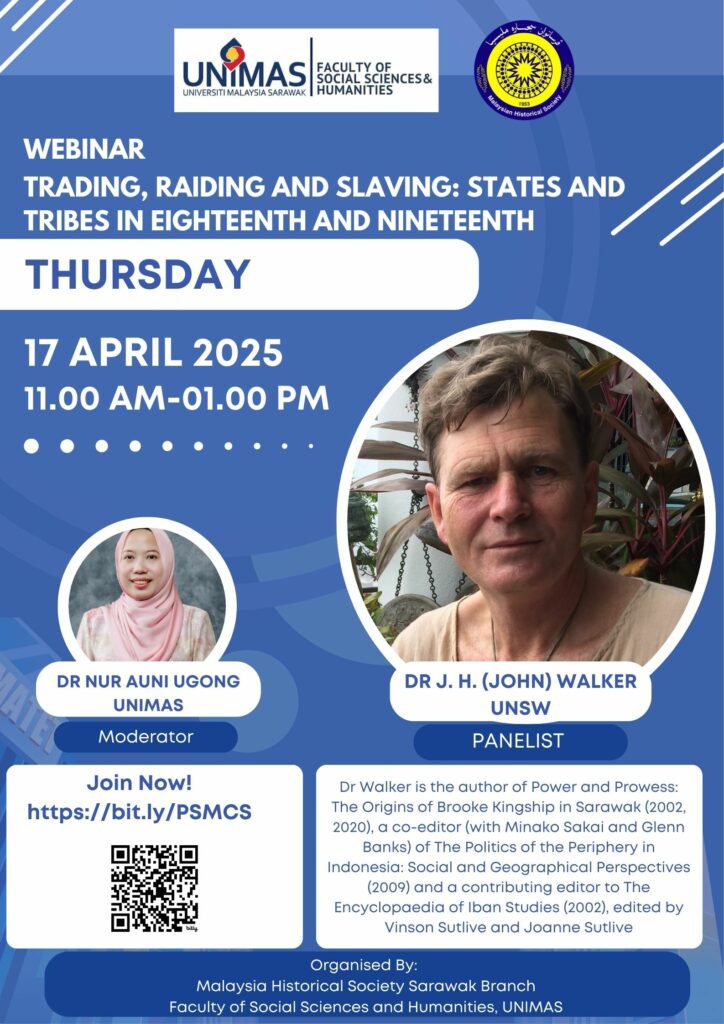

On 17 April 2025, the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS), in collaboration with the Malaysian Historical Society (Sarawak Branch), hosted a webinar featuring renowned historian Dr. J. H. (John) Walker as the keynote speaker and Dr. Nur Auni Ugong as moderator. Attended by over 200 participants, including university students, government officials, and members of the local community, the online session engage in a rich dialogue on reinterpreting indigenous political agency and diplomacy in Borneo’s precolonial past.

The discussion centred on Dr. Walker’s seminal work, Trading, Raiding and Slaving: States and Tribes in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Borneo, which challenges long-standing colonial narratives that depict tribal societies as peripheral, violent, and politically fragmented. Instead, Walker’s analysis highlights the complexity, pragmatism, and symbolic richness of indigenous governance in Borneo, inviting scholars and the broader public to reconsider how power, legitimacy, and diplomacy functioned in the region before colonial intervention.

Contrary to Eurocentric conceptions of the state as a centralized, territorially bounded entity, Bornean polities were segmentary and radiated symbolic influence through ritual diplomacy, sacred exchange, and negotiated interdependence with upland tribal groups. Trade in high-value forest commodities—such as camphor, resin, and ivory—formed the economic backbone of these relations. However, it was through ritualised gift exchange—cloth, jars, beads—and spiritual transmission that political bonds were legitimised and sustained.

The webinar illuminated how indigenous strategies such as fictive kinship, ritual combat, symbolic gifting, and selective resistance challenged the binary of domination and subjugation. The overlapping practices of trading, raiding, and slaving blurred the boundaries between state and tribe, revealing a dynamic interplay of cooperation, conflict, and co-creation of political authority. Walker’s work, and the rich discussion it sparked, not only re-centres indigenous voices in the historical record but also presents a methodological challenge: to interpret power through symbols, relationships, and spiritual dynamics rather than through the metrics of conquest and bureaucracy.

The history of state formation and inter-group relations in Borneo has often been overshadowed by colonial interpretations that framed tribal societies as violent, peripheral, and politically incoherent. However, Walker’s research calls for a reframing of that narrative, encouraging us to view the region’s past through the lens of indigenous agency, ritual diplomacy, and pragmatic political economy.

Rather than imposing control through military might or administrative systems, Bornean rulers sustained influence through symbolic relationships with upriver tribal groups who supplied valuable trade goods. These relationships were founded not merely on coercion, but on a complex web of ritual alliances, economic exchange, and mutual obligations.

A particularly compelling aspect of Walker’s analysis is his emphasis on ritual and symbolic exchange as tools of diplomacy. Instead of formal treaties or standing armies, rulers used sacred regalia, ritual oaths, and prestigious gifts, such as jars, cloth, and beads, to establish authority and mediate conflict. These exchanges were imbued with spiritual significance; for example, the gifting of cloth was seen not merely as a sign of goodwill, but as a transmission of semangat (spiritual force).

These practices disrupt simplistic narratives of domination and resistance. Tribal communities were not passive recipients of power; they actively negotiated terms, resisted when necessary, and asserted autonomy through strategic compliance, migration, and the creation of fictive kinship ties. As Walker observes, their use of land-based trade and communication routes allowed them to bypass state control over riverine pathways, subtly asserting independence.

The mutual involvement of states and tribes in trading, raiding, and slaving practices further complicates the notion of a clear divide between state authority and tribal autonomy. While modern discourse often condemns slavery, in the context of precolonial Borneo, it functioned as both a political and economic institution. Captives were sometimes assimilated through adoption, becoming labourers or even kin, reflecting the fluid nature of identity and power in indigenous society.

One vivid example Walker presents involves the Iban reconciling conflict through ritual combat using wooden weapons, a powerful symbol of peace-building and political negotiation. Other practices, such as compensatory exchanges and marriage alliances, demonstrate a deeply rooted logic of governance that prioritised relationship-building over domination.

In conclusion, Walker’s work challenges us to rethink the historical dynamics of Borneo beyond colonial binaries. By recognising ritual and symbolic exchange as central mechanisms of indigenous diplomacy, we uncover a sophisticated political system that was negotiated, performative, and deeply embedded in spiritual and cultural cosmology. This re-centering of indigenous agency not only enriches Southeast Asian historiography but also reminds us that history is more than a record of past events, it is a dialogue between worldviews.